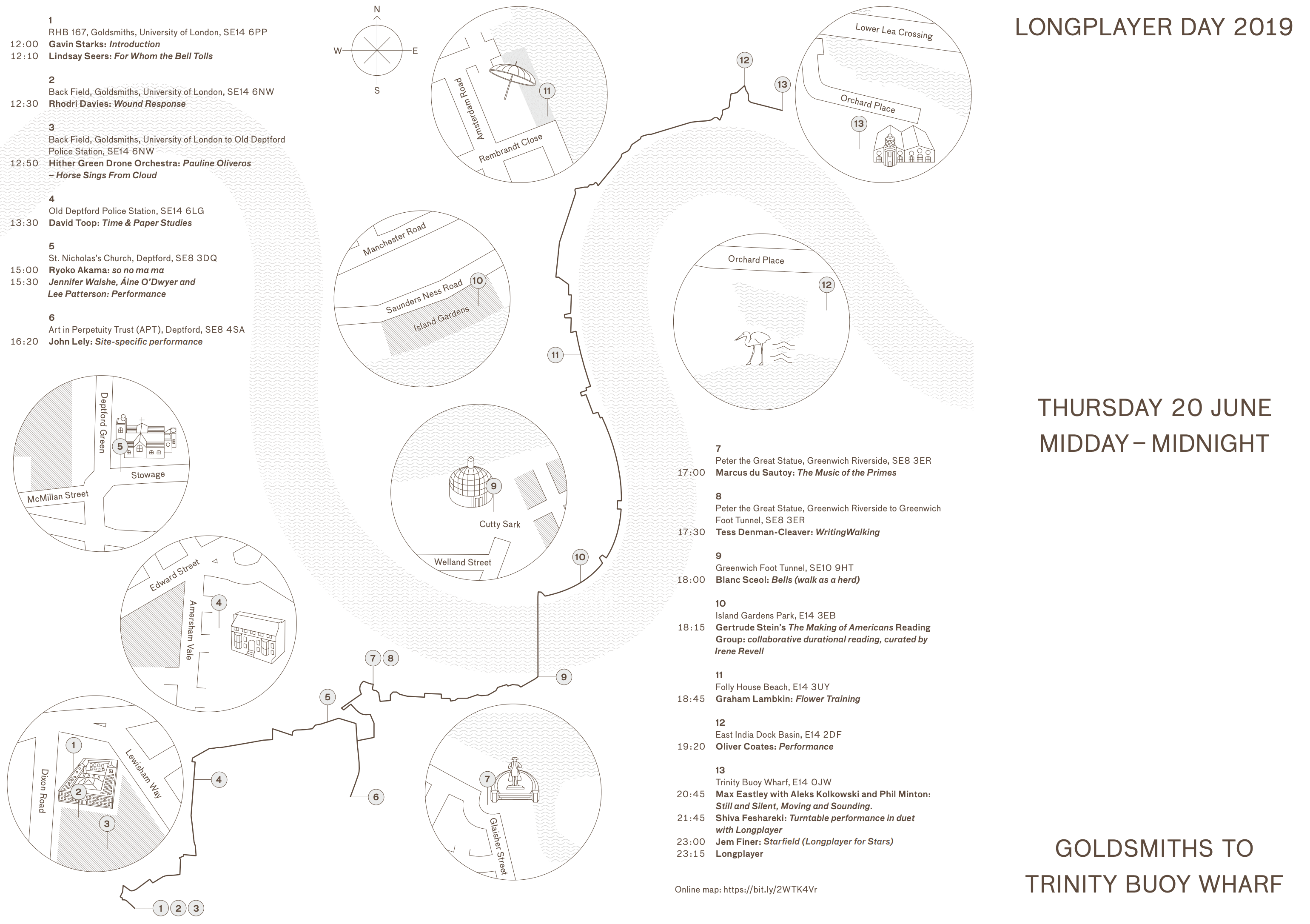

I opened the second edition of Longplayer Day, a peripatetic festival that takes inspiration from the themes and philosophies that underpin Jem Finer’s one-thousand-year-long musical composition, Longplayer.

The programme linked two locations together: Goldsmiths, University of London (New Cross) and the Longplayer listening post at Trinity Buoy Wharf (Poplar), conveying the supportive and collaborative relationship that exists between Goldsmiths and the Longplayer Trust. It began on the stroke of noon, Thursday 20 June 2019, and brought together an extraordinary programme of artists, performers and thinkers.

The programme linked two locations together: Goldsmiths, University of London (New Cross) and the Longplayer listening post at Trinity Buoy Wharf (Poplar), conveying the supportive and collaborative relationship that exists between Goldsmiths and the Longplayer Trust. It began on the stroke of noon, Thursday 20 June 2019, and brought together an extraordinary programme of artists, performers and thinkers.

A few people asked for a copy of my talk, so here is a transcription.

Hello. My name is Gavin Starks.

I’ve been working at the intersection of business, technology, science, art and media for over 20 years.

I’m one of the Trustees of Longplayer and one of my roles is to help us think through how this piece will keep going for another 1000 years, and what that might mean.

I have a lot of questions for us today.

I’ve always been interested in time — I studied both Astrophysics and Electronic Music

A few years ago, when I joined, I asked Jem about the origins of the project.

We discussed how time works ( and how clocks aren’t really helpful when thinking about it).

We talked about how we are obsessed with time, yet rarely take time; or really take time to figure out our relationship with it.

Jem recounted childhood memories with his father; of getting a telescope, looking at the stars and learning from him that they’d been there for millions of years;

He recounted tuning into shortwave radio in South America and wondering ‘what’s in between the stations?’.

Jem reflected on our sense of time: its vastness; its intangibility;

of nightmares about time;

of developing an obsession about the idea of time;

of playing music and this experience being “on the cusp of controlling time”;

that playing music time seemed almost eternal;

that ‘other times’ were “very long presents”;

and how Longplayer is still a blip.

Jem learned that stars exhibit acoustic properties and are – in effect – ringing like bells…

The singing bowls were the outcome of a long process of thinking about time, not a starting point.

Personally, I am fascinated by the ridiculous nature of time and our attempts to quantify it: from Plank time (10^-44) to the 13 billion years of Cosmological time

to the duration of a political idea — to the length of a bad joke.

How are we meant to relate to and across these ideas?

For me, one of the things that is attractive about Longplayer is just the idea of thinking on a longer timeframe, beyond your life, or you children, or grandchildren.

A 1,000 years is 30 to 40 generations.

This is at significant odds with the pace of life today.

It’s hard to imagine how to think about making something that would last 1000 years.

The Longplayer vision not only embraces this 1000 year view. It ‘repeats’.

So what does this mean? How do we begin to think about it?

We have many ways to engage around the idea — it’s not just a single piece of music.

We’ve held many events, such as today; live performances, shared letters, scores, set up listening posts, sold ‘sponsored days’ and generated conversations

In fact, Longplayer can be considered as a combination of many elements:

- An idea

- Sound

- Physical presence

- Virtual presence

- Code

- Letters

- Code

- Numbers (e.g. score, angle, time, samples)

- Algorithms

- Long ideas

- The story

- Conversations

- People

Our conversations are about the long view how can we explore which elements might be used, how, by whom, and when?

The time-frame is big — but it is still not ‘infinite’.

Longplayer helps us ask many questions about our world, and our role and meaning in its future.

It helps frame questions that are much bigger than us — from culture to climate change.

The time-bound nature of the project leads us to frame our questions about ‘what’ might be happening in the future differently.

What might our role be in that near-yet-far horizon?

What might our impact be?; how might we communicate across so many generations?

What might be happening on its fifth loop – in the year 7019?

So… How can we ensure it persists?

Firstly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, given I ran the Open Data Institute I strongly advocate that everything that Longplayer does must be open.

There are few instances in history where ‘closed’ information persists, and many that show open is the best way to spread ideas. Two simple examples, separated by some centuries: the bible and the web. Things that are open and shared tend to persist more than those that are not.

Further, If we want people to piece together the next 1000 years of our history, — we might ask: would we rather them find things as archaeological artifacts, or as the whole story, or as a curated set of outputs?

In the Netherlands, when an arts organisation –http://societeanonyme.la/ – closed down due to lack of funding, they encoded their entire works (video, sounds, photos, texts) in a printed book, the SKOR codex, copies of which are distributed around the world.

How do we take the long view?

Longplayer is not ideological, new age, nor does it represent emptiness.

It challenges us to engage to take the long view: to question what this means to us as individuals; as communities; as societies.

We question what it means to ‘be longplayer’ / to ‘be long’ / ‘belong’.

A sense of belonging seems to underpin the work—providing a mechanic for longitudinal thinking, discussion and social engagement. A sense of place that isn’t bound in where, but when.

How can we embody principles of continuity and principles of change?

We considered the question: what else has lasted, or will last, for centuries?

Religions, songs and other musics, empires (Roman, Byzantine, Venetian, Japanese), businesses (e.g. the 1000 year old Japanese hotels).

Constructions, objects and things, covering a staggering range: from Tibetan stupas to nuclear waste dumps; pyramids; statues; paintings; books; Knighthoods; tapestries; tiles; accountancy; war; standing stones; mathematics.

And so, looking forward for longplayer, do we create

- buildings in which the means to play LP awaits its players

- shared performances

- the score engraved in a rock beside a collection of singing bowls

- the score encoded in the DNA of a cockroach

- stories created and told across dinners, lunches, coffees & teas

- nursery rhymes

- events formal and informal, online and offline

- games (eg. playing cards that contain myths)

- embedded/codified in other systems (e.g. encrypted into the bitcoin blockchain)

- aboard a satellite or on a deep space mission

I think one of the reasons we are drawn to longplayer is the tension of time itself.

We feel drawn in with questions and answers that we can grasp, but know that – while it is itself time-bound – the questions and answers it raises are both timeless and infinite.

As we journey through the fantastic programme today, we will navigate through self-generating art, strings that snap, walking sonic environments, explorations of materials, found objects, opera, antique synthesiser prototypes, prime numbers, collaborative writing, bells, reading, flora & fauna, vinyl spinning, improvisation and performance.

We join Jem in celebrating long player and long thinking.

And– – as you journey, I’d like to challenge you as to how you might be…long.